When we evaluate systems that contain thin lenses, several parameters within the system may be of interest to us. At times, the distances that separate the object ( do ) and image ( di ) from a lens at hand are related to the physical dimensions of the lens itself by the Thin-Lens Equation, also known as the Lensmaker’s Equation:

( 1 / do ) + ( 1 / di ) = ( n1 – 1 )[ ( 1 / R1 ) – ( 1 / R2 ) ]

The index of refraction ( n ) is a measure of the extent that a ray of light will be bent towards ( or away from ) a central axis upon passing through a lens, and ( R ) is in reference to the radii of curvature of two imaginary spheres needed to form a lens’ front and back surfaces. In other scenarios, the Gaussian Lens Equation is used to relate the aforementioned object and image distances to the focal point and focal length ( f ) of a system:

( 1 / f ) = ( 1 / do ) + ( 1 / di )

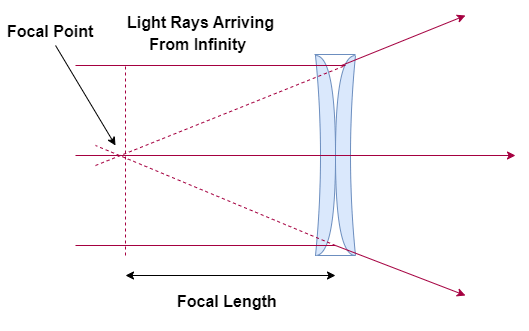

If the object in question is moved an infinite distance away from the lens, a portion of the light rays it emits will be parallel to one another when they reach the lens’ surface. If the lens in question is a convex ( a.k.a. converging ) lens, these rays will be bent inward upon passing through it. The point at which the rays converge is the focal point, and the distance separating the focal point from the lens is the focal length:

As symmetry would have it, an object that is placed at the focal point on the object side of the lens will emit diverging rays that are bent inward by the lens in such a way that they converge at infinity:

Let’s now take another look at the Gaussian Lens Equation. If the value of either ( do ) or ( di ) is increased to infinity, the corresponding term within the equation will approach zero. The term that remains will be equal to the reciprocal of the focal length of the system in question. For the sake of brevity, we’ll only consider the case where an object is moved an infinite distance away from the lens’ surface:

( 1 / f ) = ( 1 / do ) + ( 1 / di )

do → ∞

( 1 / do ) → 0

( 1 / f ) = ( 1 / di )

Under the same scenario, the Thin-Lens Equation changes in the following manner:

( 1 / do ) + ( 1 / di ) = ( n1 – 1 )[ ( 1 / R1 ) – ( 1 / R2 ) ]

do → ∞

( 1 / do ) → 0

( 1 / di ) = ( n1 – 1 )[ ( 1 / R1 ) – ( 1 / R2 ) ]

As a consequence, substitution yields the following derivation:

( 1 / f ) = ( n1 – 1 )[ ( 1 / R1 ) – ( 1 / R2 ) ]

The focal length of a lens can have a positive or negative value. This will be determined by the order in which light rays pass through a lens’ surface. In the example above where parallel rays arrive a convex lens from infinity, the first surface reached has a positive sign designation ( + R1 ), and the lattermost surface reached has a negative sign designation ( – R2 ). As a consequence, the system’s focal length has a positive value assigned to it. This focal length lies to the right of the lens, and its associated focal point is the place where light rays physically intersect. If the object in question is moved to its corresponding focal point, the order in which light passes through the lens has not changed, so this focal length, appropriately, also has a positive value. The opposite sign values will be derived if we replace the convex lens in this system with a concave lens, also known as a diverging lens:

Neither surface bulges outward, so the first surface has a negative ( – R1 ) value, and the second lens surface has a positive ( + R2 ) value. The focal length has a negative value, and rays do not physically intersect at the corresponding focal point; they only do so in a virtual manner. The same is the case when parallel rays from infinity pass from left to right through a bi-concave lens: